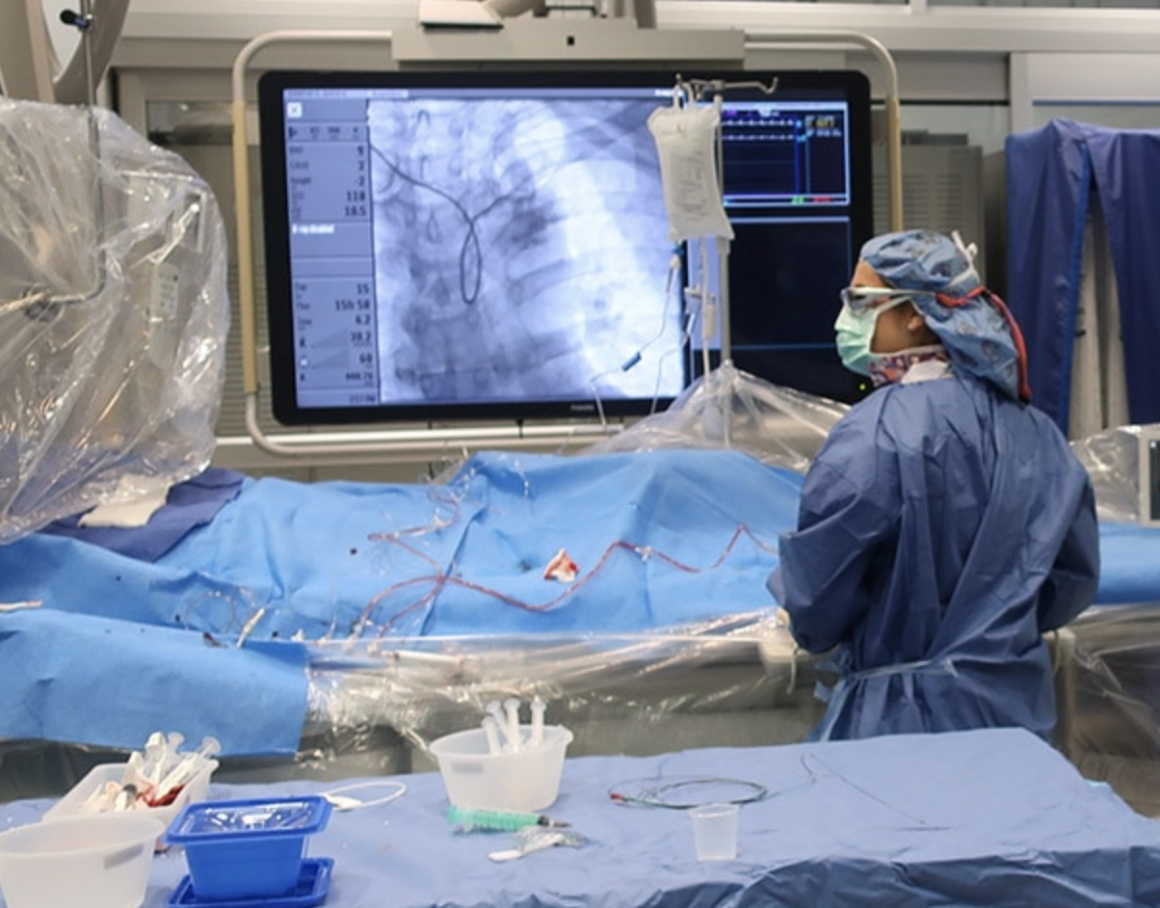

CarolinaEast Medical Center, pictured above, is leading the way in community outreach for cardiac health education in the state, earning an American Health Association Cardiovascular Center of Excellence accreditation for its efforts. The center has also been recognized for its staff training, 24/7 availability and patient care.

By Kathy Blake

More than half of Macon County rests in the Nantahala National Forest in a secluded western North Carolina pocket popular for hiking, whitewater rafting and waterfalls.

Highlands, one of the county’s two incorporated cities, sits on an Appalachian Mountain plateau 4,100 feet up and has fewer than 1,000 residents. County seat Franklin is a stop on the Appalachian Trail.

Asheville-based Mission Health, the state’s sixth-largest system with an eight-hospital network, owns Highlands-Cashiers Hospital and Angel Medical Center in Franklin.

Every three years, the two update their Community Health Needs Assessment and strategize ways to battle the same persistent beast: Heart disease is Macon County’s No. 1 killer.

In 520 square miles, nearly half of it wilderness, Macon has fewer than 35,000 people. Like its counterparts across the state, Mission is tasked with reaching a rural population to communicate coronary dangers, causes, remedies and prevention.

“Every visit, at least in my own clinic, not only talk about their coronary disease or their bypass or the stent we put in, it’s their weight control, their exercise,” says William Kuehl, Mission Health’s chief of cardiology.

The N.C. Department of Health and Human Services says Macon had from 141 to 165 annual heart disease deaths from 2013-17. Sixty-two of the state’s 100 counties had a higher fatality rate. Overall, 18,840 fatalities in 2017 — the equivalent of two per hour and 20% of all deaths — were attributed to heart disease, the state’s second-leading cause behind cancer. Stroke is third. Richmond, Bladen and Columbus counties in the south and Pasquotank County in the northeast have the highest coronary numbers, at 229 to 302 in that four-year span.

North Carolina is in the 11-state Stroke Belt, where minimal exercise and unwholesome diets drive heart disease risk 34% higher than in other areas of the country. One factor is location: Eighty of 100 counties are considered rural, with fewer than 250 persons per square mile. About 40% of the population, or 4 million people — second only to Texas — live away from urban areas. Hospitals are fighting back with outreach, technology and surgical advances.

“One thing we did was to be more proactive in getting people to be active, knowing that heart disease is associated with people who are not moving or eating healthy,” says Bonnie Peggs, manager of community relations and hospital chaplain in Franklin, who co-authored the needs assessment.

Angel initiated a free Passport to Wellness program, which includes seven annual community events such as tobacco education classes, health fairs, blood pressure and glucose checks, and stroke assessments. “Every week, we encourage business people to meet with us and walk the paved greenway walking trail during lunch,” Peggs says.

Hospitals across the state are pushing into the outskirts of their coverage areas to fight obesity, tobacco use, high blood pressure and lack of physical activity.

Atrium Health

Atrium HealthKevin Lobdell, Atrium Health’s director of regional cardiac, vascular and thoracic surgery quality, education and research, explains the state’s rural areas are harder to reach, contributing to unhealthy habits that drive heart disease.

Charlotte-based Atrium Health’s The Perfect Care: Personalized Cardiac Care and Collaborative, an initiative funded by a $1.1 million Duke Endowment grant, launched in the first quarter and will enroll its first patients later this year. It’s designed to reach 10,000 people in the next two years.

Greenville-based Vidant Health’s coverage area is 1.4 million people in 29 counties east of Interstate 95. In January, three medical group clinics — ECU Physicians’ Adult Medicine and Pediatric clinic, Vidant Internal Medicine-Greenville and Vidant Family Medicine-Greenville — were awarded Gold Status for Target: Blood Pressure by the eastern Carolina chapter of the American Heart Association.

“We do screenings throughout the year,” says Dustin Austin, Vidant’s service administrator for heart and vascular care, “and during February [Heart Health Month] we partner with the American Heart Association and do a slew of events.”

In Fayetteville, Cape Fear Valley Health System, which serves six eastern counties including Harnett, has expanded its network of primary care clinics to give rural residents care closer to home and upgraded its services at Central Harnett Hospital.

A North Carolina health care system leading the way in cardiovascular health is Carolina East Medical Center in New Bern, the first hospital in the state to receive the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Cardiovascular Center of Excellence Accreditation. This accreditation level is reserved for medical centers the AHA believes is exceeding standards in cardiovascular services, comprehensive staff training and community outreach. According to a Carolina East Health System press release, the hospital underwent a tough review process to receive the accreditation and was specifically noted for its care of patients with chest pain, atrial fibrillation and heart failure.

FirstHealth Moore Regional Hospital in Pinehurst was honored in February by the North Carolina Healthcare Association with the inaugural NCHA Healthier Communities Award for its implementation of The Daily Mile. It is the first hospital in the U.S. to use the physical activity program for children that began in the United Kingdom.

Looking at the younger population is the impetus behind The Daily Mile. Moore Regional’s First-in-Health 2020 Task Forces worked with Richmond and Montgomery County schools to secure 15 minutes each school day for every elementary student to walk, jog, run, skip — whatever they choose — apart from physical education class or recess. FirstHealth spent $232,000 to build walking trails on 14 school campuses and received a Duke Endowment grant in 2015 for its Healthy People, Healthy Carolinas initiative for building the first trails. The trails may be used by the public after school hours.

First Health

First HealthFirstHealth Moore Regional in Pinehurst was honored in February by the North Carolina Healthcare Association for its implementation of The Daily Mile, a physical activity program for children aimed at preventing cardiac issues later in life.

In two years, The Daily Mile data has charted an estimated 409,293 miles walked by Richmond and Montgomery children and adults.

Lillington, which has a population of 3,500, takes up 4.6 square miles of central Harnett County along the Cape Fear River about 31 miles south of Raleigh and 27 miles from Fayetteville. Cape Fear Valley Health operates a Heart and Vascular Center in Fayetteville and, in 2018, opened a $2.5 million heart catheterization lab at Central Harnett Hospital, bringing specialized cardiac service to the area for the first time.

Amol Bahekar, an interventional cardiologist at Cape Fear Valley Heart & Vascular Center, explains heart disease causes and prevention measures to patients in his practice. “We’re trying to spread knowledge to the general population,” he says. “I talk to them about risk and I focus on exercise and diet and taking their medicine regularly. Smoking is a big part of my counseling with these patients.”

Metropolitan areas are not exempt from limited health care access. A study by ONE Charlotte Health Alliance — a collaboration among Atrium, Novant Health and the Mecklenburg County Health Department — found 22% of Mecklenburg adults did not have a regular source of care, and 20% could not see a doctor because of cost.

In addition to its $1.1 million for Perfect Care, the Duke Endowment put $480,000 toward “food pharmacies,” two refrigerated vehicles that deliver food to residents of lower-income areas.

Even with lifestyle changes, acute episodes of heart failure — when blood is no longer pumping as well as it should be — are a leading cause of hospitalization. Atrium’s Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute uses the Heart Success Program, a 30-day holistic, multidisciplinary team approach to managing heart failure and avoiding repeat hospitalization. The program is available at five Atrium hospitals and in three counties via virtual visits.

“Heart Success is five days a week,” says Sanjeev Gulati, the institute’s medical director of heart failure and transplant services. “Each day, the provider, a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, works with a team that consists of one of each — registered nurse, social worker, pharmacist, dietician, community paramedic, health advocate and clinical staff. There is also a nurse navigator that is dedicated to heart failure. Part of our job is to educate them so they can get on the right track and take their disease seriously,” he says.

Readmissions, he says, are less than 14% — compared with a national average of 21% to 25%.

“When it comes to health care, rural areas often have the bigger challenges to face,” says Kevin Lobdell, Atrium’s director of regional cardiac, vascular and thoracic surgery quality, education and research.

Cloud-based electronic health records software Perfect Care EHR, he says, can provide virtual access to individualized recovery care for cardiac patients. “We are eliminating disparities in follow-up care by reducing patients’ burdens of traveling to and from appointments,” he says.

Initially, Lobdell says, Perfect Care is being added at Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center, Atrium Health Pineville and Carolinas HealthCare System Northeast in Concord and will include three other Atrium facilities in the next two years.

“We also aim to share the lessons learned with other health care organizations and elevate these efforts for population health,” he says.

Advances in coronary and vascular procedures are many. “Most things I use in the cath lab had not even been invented when I came here in 1992,” says Mission’s Kuehl.

Mission has one helicopter in Franklin and two in Asheville. In the past year, Mission received 650 people in the process of a major heart attack, by air or by ambulance. The national guideline for getting patients to intervention is 90 minutes or less. Asheville averages less than 44. In the east, New Hanover Regional Medical Center averages 35 to 40 ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction heart attacks per month using its AirLink aircrafts stationed in Jacksonville, Whiteville and Brunswick County.

Kuehl says several recent advances in care are making an impact. The left ventricular assist device is a pump that screws into the heart to help augment pumping. “Heart transplants are so rare now, so the LVAD is a huge thing,” he says. “For someone with a completely failing heart, it improves the pumping.”

Cape Fear Valley Health

Cape Fear Valley HealthAdvances in heart procedures such as the transcatheter aortic valve replacement have brightened patient outcomes in intermediate and high-risk cases. But prevention of cardiac diseases requires personal changes in diet and exercise for patients.

The HeartMate 3 LVAD system received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval last fall as a method to continue pumping blood from the left ventricle to the aorta.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement, approved in 2012, has been used at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and UNC Healthcare in Chapel Hill, as well as Cape Fear Valley Health, New Hanover Regional, Moore Regional’s Reid Heart Center and Vidant for high-risk patients. More recently, it has been approved for intermediate-risk cases.

And the MitraClip, a procedure to correct leaking through the mitral valve, which can cause heart failure, is done through a small incision in the groin. A catheter is moved through the leg to the heart, where a clip is placed on the leaking valve. “The trend is seeing less opening of the chest and more of going through the leg, to avoid open heart surgery altogether,” Kuehl says.

New Hanover Regional is among hospitals preparing to add MitraClip.

“We are employing advanced technologies such as the Impella device and ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] to treat even the most ill heart failure patients,” says Christopher Ellis, cardiologist with New Hanover Regional Physicians Group’s Cape Fear Heart Associates. The Impella is a tiny LVAD that can pump blood via a 5-millimeter device inside a catheter.

Last year, Moore Regional was among the first to provide Medtronic’s Micra transcatheter pacing system — one-tenth the size of traditional pacemakers. It is implanted directly into the heart via a catheter. Mission Health is the first in western N.C. to offer the new pacemaker, which weighs about the same as a penny.

And the Watchman, approved by the FDA in 2015, is an implant that can reduce stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation and one of many advances common at Vidant, New Hanover and other centers.

“For A-fib, one of the biggest causes for concern is stroke. We treat that with blood thinners because the top chamber does not squeeze right and clots can form,” says Brian Cabarrus, an interventional cardiologist, medical director of Vidant Cardiology and medical director of structural heart at Vidant Medical Center. “The Watchman can close the [left atrial appendage] area.”

Cabarrus says TAVR and other minimally invasive processes have brightened patients’ outlooks. “The fact is that people you thought had no chance of surviving in the past are going home and doing well. People who come in [with] cardiac arrest, now there’s a good chance they’re going to be fine.”

Like cardiologists across the state, Cabarrus emphasizes personal choices. “It’s really hard to follow some specific diets in eastern North Carolina, because that is not our culture. But you have to pick what you can live with,” he says. “Nobody’s perfect. If you go to McDonald’s 10 times a month, cut it to two. What can you do and stick with long-term? It’s kind of personal, because I’m from around here, and you want people to have better care. Because one day it will be your mom or your dad.”